| Hint | Food | 맛과향 | Diet | Health | 불량지식 | 자연과학 | My Book | 유튜브 | Frims | 원 료 | 제 품 | Update | Site |

|

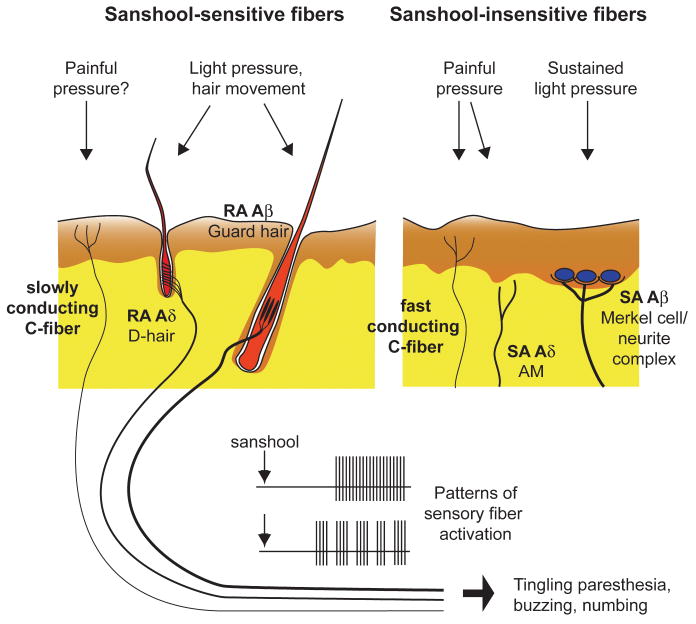

맛의 종류 ≫ 매운맛 ≫ 캡사이신 향신료 : 사천후추 sanshool 향신료의 종류 - 육두구 Nutmeg, mace - 마라 사천후추 snashool - 온각 : Vanilloid receptor - 캡사이신 : 매운맛 단위 : 스코빌 - 찬맛(냉미, Cooling) : 멘톨 사람들은 정말 지루한 것을 싫어한다. 그래서 맛의 기본은 자극이다. 친숙하고 익숙하고 좋은 자극이면 바로 좋아하게 되고, 통증이 되는 자극도 몸에 나쁘지 않으면 이내 적응하여 좋아하게 된다. 향신료는 향으로 후각을 자극할 뿐 아니라 온도감각이나 촉각을 자극하여 우리에게 새로운 자극을 준다. 고추의 캡사이신, 겨자나 와사비의 isothiocyanate, 마늘의 알리신, 박하의 멘톨은 온도수용체를 자극하는데 구체적인 수용체가 달라 그 느낌이 다르다. 그런데 최근 인기를 얻고 있는 마라의 Sichuan pepper에는 후각과 온도감각 말고도 추가적인 자극이 있다. 바로 촉각이다. 초피에는 캡사이신의 매운맛과는 다른 '얼얼한 맛(마痲)'이 있는데 산쇼올(sanshool) 덕분이다. 초피를 많이 뿌린 음식을 먹다보면 입술이나 혀, 입천장을 비롯한 입안 여기저기가 저리고 얼얼한 걸 느낄 수 있다. 입에는 미각, 온각, 촉각 등이 같이 있는데 산쇼올은 가벼운 접촉을 감각하는 수용체( Aβ and D-hair neurons)를 활성화시킨다. 온도수용체가 온도에만 반응하여야 하는데, 실수로 캡사이신에도 반응하는 것처럼 촉각이 실수로 산쇼올이라는 화학물에도 반응하는 것이다. 2013년 영국의 유니버시티 칼리지 연구팀은 산쇼올 성분을 입술에 발랐을 때 초당 50회 진동하는 것과 비슷한 자극이 일어나는 것을 확인하기도 하였다. 사람들은 시간이 지날수록 동일한 자극을 지루해하고 좀 더 강한 자극을 원하지만 단일한 자극이 너무 강한 것에는 거부감이 있다. 마라에는 우리에게 익숙한 온도자극 성분도 있지만 약간 다른 촉각 자극도 마져있다. 더구나 통증이 아닌 부드러운 촉각을 감각하는 수용체이다. 이것이 새로운 매력으로 느껴질 수 있다. 향신료의 일종으로 학명은 Zanthoxylum piperitum. 제피, 지피(경상도), 젠피(전라도), 조피(이북), 남추, 촉초라고도 한다. 영어로는 Sichuan pepper라고 하는데 쓰촨 후추라는 뜻이다. 초피나무는 쥐손이풀목 운향과 초피나무속 낙엽관목이다. 원산지가 중국 쓰촨 지방이기 때문에 촉에서 온 향신료라는 뜻으로 '촉초'라고 부르기도 한다. 중국에서 '화자오'(花椒)라고 부른다. 산초(Zanthoxylum schinifolium)하고는 친척으로, 실제로도 열매만 보면 그놈이 그놈 같을 정도. 게다가 일본에서는 초피를 산초라 부르기 때문에 더욱 혼동되어 사용되고 있다. 산초로는 기름을 만들 수 있지만 초피로는 기름을 만들 수 없다. 가시가 마주 났는지, 아닌지로 구분이 가능하다. 초피의 맛은 '매운맛'이라기보다는 '얼얼한 맛(마痲)'이라고 한다. 마파두부의 다섯 가지 맛(랄ㆍ향ㆍ색ㆍ탕ㆍ마) 중 '마'가 초피의 얼얼한 맛알 가리키는데, 산쇼올(sanshool)이 주 요소이다. 맛은 '비누맛이 난다'고 처음 먹거나 거부감이 드는 사람들은 그럴 정도지만, 보통 '얼얼한 맛'이라고 말한다. 실제로 좀 많이 뿌린 음식을 먹다보면 입술이나 혀, 입천장을 비롯한 입안 여기저기가 저리고 얼얼한 걸 느낄 수 있다. 마파두부 이외에도 중국 사천 요리에 특히 많이 들어가는 향신료이다. 초피나무는 주로 산중턱이나 산골짜기에서 나지만 산기슭은 물론이고 밭 주변에서도 흔하게 자란다. 키는 3~5m로 헌칠하게 자라고, 턱잎이 변한 1㎝ 정도 작은 가시가 잎자루 밑에 1쌍씩 마주 달린다. 또 잎은 어긋나기 하고, 아카시아처럼 잎줄기 좌우에 여러 쌍의 진초록 잔잎이 짝을 이루어 달리고, 끝자락에 잎 하나 붙는 깃털 모양의 잎(홀수깃꼴겹잎)이다. 잔잎(소엽, 小葉)은 달걀 모양으로 길쯤한 잎줄기에 9~11장씩 어긋나게 달린다. 잎의 앞면 가운데에 노랗고 반투명한 기름방울(유적, 油滴)이 나오는 검은 기름 점(유점, 油點)이 있다. 제피나무의 어린잎은 데쳐서 묻혀 먹거나 생채로 고추장에 박아 장아찌를 담그며, 열매껍질은 향신료(香辛料)로 사용한다. 열매껍질을 ‘제피’라고 부르는데, 이것을 잘 말려 절구통에 찧어서 병에 담아두고 조금씩 쓰는데 가루 상태로 오래 저장하면 점차 매운맛을 잃게 되므로 열매로 간수했다가 사용 직전에 갈아 쓰는 것이 더 좋다(후추도 매한가지이다). 대충대충 거칠게 간 가루를 추어탕에 넣어 비린내를 잡아 주고, 매운탕·김치·된장찌개에도 넣어 먹는데, 매콤한 맛과 코를 톡 쏘는 매운 향인 산쇼올(sanshool)은 혀끝이 아린 듯 얼얼한 느낌을 준다. 제피에는 기름 성분이 2~6% 들었는 데, 그중 산쇼올이 8% 정도 들었고, 강하고 자극성이 있어 미각과 후각을 마비시킬 정도다. 정유(精油)에서 얻어지는 향기 성분인 리모넨(limonene, dl-dipentene), 게라니올(geraniol), 시트로넬랄(citronellal)과 매운맛 성분인 산쇼올(sanshol), 크산톡신(zanthoxyn)이 들어 있다. 크산톡신은 마취 성분이 있어서 산초나무잎을 짓찧어서 개천에 풀면 물고기가 경련으로 가사 상태가 되는 정도이므로, 산초나 초피를 너무 많이 먹는 것은 좋지 않다. 열매의 매운맛 성분은 살균 작용이 있으며 구충 효과도 있고, 정유 성분은 살충 효과가 있다. 약용은 열매가 익어 갈라질 무렵에 채취한다. 한방에서는 열매의 껍질을 ‘야초(野椒)’라는 약재로 쓰는데, 복부의 냉증을 제거하고 구토와 설사를 그치게 하며, 회충·간디스토마·치통·지루성 피부염에 효과가 있다. 예로부터 산초나무 열매 기름은 민간에서 위장병이나 기관지천식, 부스럼 등의 치료제로 이용하였다. 최근에는 산초나무 종자에서 추출한 정유 물질이 국부 마취 및 진통 작용이 있고, 대장균·구균류·디프테리아균 등에 항균 작용이 있는 것으로 보고되었다 ------------- 월요병에 축 처진 당신, 오늘 매운맛 좀 볼래요? [중앙일보] 입력 2015.12.07 02:17 강혜란 기자 여기에 요즘 색다른 매운맛이 더해졌다. 중국 쓰촨(四川) 요리로 대표되는 ‘마라(麻辣)’다. 마라란 중국어로 ‘맵고 얼얼하다’라는 뜻이다. 이 매운 느낌이 우리가 여태 먹었던 매운맛과 다르다. 볶음 요리인 마라샹궈나 샤브샤브인 훠궈 모두 기묘하게 얼얼하다. 무엇이 다른 것일까. 이제까지 매운맛은 어디서 온 것일까. # 입술이 마비될 듯 아린 맛=쓰촨 요리에서 매운맛의 주역은 ‘쓰촨 산초(학명 Zanthoxylum simulans)다. 한국에서 산초(山椒)라고 불리는 것(학명 Zanthoxylum schinifolium)과 다른 종류다. 쓰촨 지방을 대표하는 향신료로 초피나무 열매다. 여기 3% 포함된 하이드록시 알파 산쇼올(hydroxy alpha sanshool)이라는 성분이 얼얼함의 주역이다. 고추의 캡사이신 성분은 속이 타면서 열이 오르는 듯한 느낌을 준다. 이 성분은 신경세포가 열 감각을 받아들이는 수용체 TRPV 중 43도 이상의 열을 감지하는 TRPV1을 자극한다. 마치 고온으로 피부에 화상을 입는 것과 같은 자극이다. 반면 쓰촨 산초의 매운맛은 입안이 아리면서 입술이 마비되는 느낌이다. 영국의 유니버시티 칼리지 런던 연구팀에 따르면 산쇼올 성분이 든 산초액을 입술에 발랐을 때 초당 50회 진동(50헤르츠)하는 듯한 자극을 받는 것으로 조사됐다. 이 진동은 피부 진피에 있는 돌기 안에 위치한 마이스너소체(촉각소체)를 자극한 것으로, 마이스너소체는 피부에서 떨리는 자극에 반응한다. 대신 산쇼올 성분은 산초를 말려 가루를 낼 경우 공기 중에 증발되어 없어져 버린다. 추어탕에 넣는 산초가루에서 얼얼한 맛을 느끼기 힘든 이유가 이 때문이다. [아무튼, 주말] 쓰촨식 매운 맛 얼얼한 마라의 매력 이해림 푸드 칼럼니스트 2019.04.06 03:00 “중국 일초 수입량이 몇 해 사이 20~30%가량 증가했습니다. 대신 쥐똥고추는 일초 수입량이 증가한 만큼 줄어들었죠.” 연 45억원 이상 매출 규모로 고추를 대량 취급하는 경동시장 대광고추 안효충 대표의 이야기다. 쥐똥고추는 매운 닭발, 갈비찜, 족발 등이 유행하는 동안 수입량이 증가했던 동남아 고추다. 땀 뻘뻘 나는 그 매운 양념 맛의 비결이었다. 일초는 쥐똥고추보다는 덜 맵고, 청양고추보다는 두 배가량 매운 중국 고추 품종. 마라 요리에 필수적으로 사용된다. 매운 맛의 취향이 대륙으로 옮겨 갔다. 색다른 매운 맛, 마라麻辣 열풍 중국 쓰촨에서 온 마라麻辣 열풍은 이제 그 누구도 말릴 수 없다. 시작은 몇 해 전, 화양동, 대림동, 구로동 등 새로 형성된 서울 속 ‘차이나 타운’에서부터였다. 중국의 동북 지역 음식, 대표적으로 양꼬치 일색이던 중국 거리에 쓰촨 중식 전문점이 실시간으로 등장하기 시작했다. 중국에서도 쓰촨 음식은 거국적 인기다. 중국인 거리와 대학가를 중심으로 한 폭발적인 흐름은 이제 평범한 거주지역 골목까지 번져 왔다. 하이디라오, 마카오도우라오 같은 현지 훠궈 체인점이 한국에 진출했고, 훠궈 체인점에서 단체 모임을 갖는 중장년층 모습도 제법 자주 볼 수 있다. 쿵푸功夫를 돌림자마냥 쓰는 여러 마라탕 체인점이 마치 김밥천국처럼 흔하게 동네 어귀까지 생겨나고 있다. 분식 체인점서부터 패밀리 레스토랑, 심지어 베트남 음식 체인점마저. 외식업계에선 가릴 것 없이 앞다투어 마라 메뉴를 도입하고 있다. 한국인의 소울 푸드, 치킨도 예외는 아니다. BBQ에서 마라 양념에 버무린 ‘마라핫치킨’을 판매 중이다. 또다른 소울 푸드인 떡볶이 또한 마라 열풍을 피하지 못했다. 양념에 마라 향을 더한 마라떡볶이로 퓨전됐다. 요사이 유튜버 사이에선 훠궈 재료인 콴펀宽粉(납작한 중국 당면), 펀하오즈粉耗子(가래떡 모양 당면)를 떡볶이에 넣어 먹는 콘텐츠가 쏟아져 나오고 있다. 도시인의 간편한 밥상 역할을 하는 편의점도 마라 일색. CU 편의점이 의욕적이다. 작년 출시한 CU 마라탕이 출시 3개월만에 15만 개 팔렸다. 지난 3월 매출신장률은 출시 초 대비 91.9%에 달했다. 그 기세를 이어 지난 3월 말에는 마라볶음면을 위시해 김밥, 삼각김밥, 도시락, 만두, 과자에 즉석 안주류까지 다양한 제품군의 마라 라인업을 대거 출시했다. 쓰촨식 마라 요리는 한국 식문화의 일부로 뜨겁게 자리 잡았다. 마라, 얼얼하고 매운 맛의 신세계 그래서 대체 마라란 무엇인가. 마라는 중국의 4대 요리 중 하나인 쓰촨 중식의 핵심이다. 마늘, 후추, 생강, 화자오, 고추 등이 쓰촨 맛의 기본인데, 그 중 화자오와 고추가 내는 맛이 곧 마라다. 맛을 표현하자면 ‘맵다’ 대신에 ‘마라하다’라는 신조어로 설명해야 하는 성질의 것이다. 매운 맛인 라辣는 우리도 무척 잘 알고 있는 것과 동일한 매운 맛이다. 고추의 익숙한 매운 맛이 라다. 마麻는 엄밀히 맛이라기보다는 물리적인 자극에 더 가깝다. 후추, 산초, 제피와 비슷하게 생긴 화자오花椒에서 비롯된다. 화자오는 레몬과 같은 종류의 새콤한 향과 맛을 갖고 있으면서 독특한 전기 자극을 전달하는 향신료다. “화자오에 함유된 산쇼올은 독특한 작용을 합니다. 미세한 진동처럼 느껴지는 촉각 자극을 주죠. 덕분에 마라 요리를 먹으면 얼얼한 느낌이 입에 바로 옵니다.” 과학적으로 맛을 분석한 ‘맛의 원리’를 쓴 식품공학자 최낙언 씨의 설명이다. 고추의 캡사이신은 뜨거운 온도로 느껴지는 매운 맛을 내는 데 비해 화자오의 산쇼올은 마취주사를 맞은 듯 멍한 마비감을 준다. 불타오르는 매운 맛, 그리고 새콤하고 얼얼한 감각이 더해진 것이 쓰촨 중식의 맛, 마라다. 훠궈∙마라탕∙마라샹궈∙촨촨… 이름만큼 낯설고도 별난 맛 한국에서 마라 요리 3대장으로 꼽을 만한 메뉴는 쓰촨식 훠궈, 마라탕, 그리고 마라샹궈다. 훠궈는 마라하고 기름진 홍탕, 버섯이나 사골, 채소로 흰 육수를 낸 백탕, 새콤달콤한 토마토탕 등 육수 두 세가지를 원앙냄비에 끓여 고기와 해산물, 채소 외에도 갖가지 두부, 당면 등 재료를 조금씩 담가 익혀 먹는다. 원하는 재료를 한 접시씩 주문하다 보면 인당 3~4만원 훌쩍 넘는 계산서를 받게 되는 고급 훠궈부터 인당 1만원대 후반의 무한리필 훠궈부페까지 가격대 스펙트럼이 넓다. 마라탕은 훠궈의 홍탕과 거의 비슷한 국물 요리다. 훠궈는 식탁에서 끓여가며 먹고, 마라탕은 식당 주방에서 끓여낸다는 것이 가장 명확한 차이. 일품요리로 국수를 말아 마라탕면으로 내는 곳도 있고, 냉장 쇼케이스에 진열된 재료를 원하는 만큼 고르고 중량대로 값을 매기는 부페식 마라탕 전문점도 있다. 마라샹궈는 볶음 요리. 마라 양념에 갖가지 재료를 볶아낸 음식이다. 마라탕처럼 부페식으로 재료를 고를 수 있는 곳도 있고, 정해진 재료대로 알아서 만들어주는 곳도 있다. 한 가지 더 꼽자면 마라롱샤도 있다. 롱샤라는 작은 가재를 마라 양념에 볶아낸 이 음식은 영화 ‘범죄도시’를 통해 세간에 요란하게 알려졌는데 발라 먹기가 성가셔서인지 최근엔 인기가 시들었다. 마라탕과 마라샹궈에도 공통적으로 사용되는 재료들이다. 위 왼쪽부터 순서대로 등홍고추와 초고추, 초과와 감초와 팔각, 고강량과 백지, 월계수잎과 산약, 계피, 청 화자오와 홍 화자오, 생 화자오, 즈란. 둘째 줄은 훠궈에 들어가는 단백질 재료들. 왼쪽부터 차례대로 양고기, 소시지, 새우완자, 만두, 피두부, 푸주腐竹, 얼린 두부. 현지에서는 선지나 내장류뿐 아니라 뇌, 혀, 발 등 더 다양한 단백질 재료를 먹는다. 아래는 채소류와 탄수화물 재료. 왼쪽부터 청경채, 감자와 연근, 배추와 단호박, 콴펀, 펀하오즈, 목이버섯, 표고버섯과 느타리 버섯. / 사진=이신영·김종연 기자  Physiological basis of tingling paresthesia evoked by hydroxy-α-sanshool Richard C Lennertz,1 Makoto Tsunozaki,2 Diana M Bautista,2 and Cheryl L Stucky1 Our data demonstrates that the majority of fibers activated by sanshool are Aβ and D-hair neurons that mediate the detection of light touch, rather than noxious stimuli. However, there is a subset of C-fibers that do respond robustly to sanshool. Hydroxy-α-sanshool, the active ingredient in plants of the prickly ash plant family, induces robust tingling paresthesia by activating a subset of somatosensory neurons. However, the subtypes and physiological function of sanshool-sensitive neurons remain unknown. Here we use the ex vivo skin-nerve preparation to examine the pattern and intensity with which the sensory terminals of cutaneous neurons respond to hydroxy-α-sanshool. We found that sanshool excites virtually all D-hair afferents, a distinct subset of ultra-sensitive light touch receptors in the skin, and targets novel populations of Aβ and C-fiber nerve afferents. Thus, sanshool provides a novel pharmacological tool for discriminating functional subtypes of cutaneous mechanoreceptors. The identification of sanshool-sensitive fibers represents an essential first step in identifying the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying tingling paresthesia that accompanies peripheral neuropathy and injury. Sanshool-evokes periodic burst firing in sensory fibers In a subset of fibers, sanshool evoked a burst pattern of action potential firing (Figure 6A). Bursting was most prevalent among sanshool-sensitive C-fibers and D-hair fibers, occurring in 73% and 26% of sanshool-sensitive fibers, respectively. Large myelinated Aβ fibers were the least likely to show bursting as only one Aβ-RA fiber exhibited bursting and none of the Aβ-SA fibers displayed bursting (Figure 6A). Interestingly, the rapidly adapting D-hair fibers and slowly adapting C-fibers displayed distinct patterns of burst firing. Rapidly adapting D-hair fibers (and the Aβ-RA fiber) issued quick bursts of action potentials with short intervals, whereas the slowly adapting C-fibers issued significantly longer-duration bursts of action potentials at less frequent intervals (Figure 6B, right). Consequently, the average number of action potentials per burst was considerably higher in C-fibers than in D-hair or RA-Aβ fibers (Figure 6B, left). These data suggest differences in the membrane dynamics of rapidly and slowly adapting fibers. Discussion Here, we sought to identify the subtypes of sensory neurons that underlie the tingling paresthesia elicited by hydroxy-α-sanshool. Our findings show that sanshool is the first pharmacological agent identified that can discriminate between distinct subsets of mechanosensory neurons (Figure 6). Among Aδ fibers, virtually all D-hair afferents were vigorously excited by sanshool, whereas AM nociceptors were completely unresponsive. D-hair afferents are the most sensitive of all mechanoreceptors, with mechanical thresholds below the measurable limit (Brown and Iggo, 1967; Burgess et al., 1968; Koltzenburg et al., 1997). They are a key fiber type required for normal tactile acuity and movement detection (Brown and Iggo, 1967; Wetzel et al., 2007). In addition, D-hairs have also been implicated in diabetic peripheral neuropathy (Jagodic et al., 2007; Shin et al., 2003), which often leads to tingling paresthesia in patients. Sanshool also activated rapidly adapting Aβ mechanoreceptors that encode the movement of guard hair follicles. Similar to rapidly adapting Aδ D-hair receptors, sanshool was more potent in activating Aβ fibers with rapidly adapting properties to mechanical force than those with slowly adapting properties. Thus, among all myelinated fibers, sanshool activates rapidly adapting fibers far more extensively than slowly adapting fibers. Spontaneous activity in rapidly adapting myelinated fibers has been implicated in both injury- and disease-evoked paresthesia, as well as in post-ischemic paresthesia; however, the exact neuronal subtypes that mediate tingling paresthesia have not been characterized (Nordin et al., 1984; Ochoa and Torebjork, 1980). A subset of slowly-adapting Aβ fibers also responded to sanshool, albeit with lower firing intensities. Most slowly adapting Aβ fibers are thought to be “SA-I” that innervate Merkel cells and encode sustained pressure to skin, but some slowly adapting Aβ fibers are “SA-II” and sense skin stretch (Srinivasan et al., 1990; Lamotte et al., 1998). Interestingly, in rat 35% of slowly adapting Aβ fibers in the sural nerve and in mice 52% of slowly adapting Aβ fibers in the saphenous nerve are reported to be SA-II stretch sensors (Leem et al., 1993; Maricich et al., 2009). Furthermore, a distinguishing feature of SA-II receptors is that they are approximately six times less sensitive to skin indentation than SA-I receptors (Johansson and Vallbo, 1979, 1980). Two findings support the idea that the sanshool-sensitive slowly adapting Aβ fibers are SA-II type skin stretch sensors. First, the proportion of sanshool-sensitive slowly adapting Aβ fibers (36%) is consistent with the proportion of SA-II type skin stretch sensors. Second, the sanshool-sensitive SA-Aβ fibers were ∼5 fold less sensitive to sustained force than the sanshool-insensitive population. Sanshool activated a unique subset of C-fibers that has an intrinsically slower conduction velocity than other C-fibers. Conduction velocity is largely dependent on fiber diameter and myelination which influence the internal resistance and membrane capacitance of nerve axons. Thus, we may observe this difference because sanshool-sensitive channels are expressed on the smallest diameter C-fibers. However, conduction velocity also correlates with the length constant of a nerve fiber, which is directly proportional to membrane resistance (Koester and Siegelbaum, 2000; Hodgkin and Rushton, 1946). An intriguing possibility is that sanshool-sensitive channels, potentially KCNK18 channels, decrease membrane resistance and thereby, directly slow the conduction velocity. Previous studies of tingling paresthesia in humans have failed to report aberrant activity of Aδ or C-fibers (Nordin et al., 1984; Ochoa and Torebjork, 1980). However, this may be due to technical difficulties in recording from patients experiencing tingling paresthesia. Our data implicate both D-hair afferents and the unique population of slowly conducting C-fibers in tingling paresthesia. Our data lend support to the hypothesis that sanshool elicits tingling paresthesia through selective activation of mechanosensitive somatosensory neurons (Figure 6). Human psychophysical testing shows that sanshool exhibits its sensory effects ∼60 seconds after application (Bryant and Mezine, 1999). Our behavioral data show that mice respond to the effects of sanshool with a characteristic latency of 50 seconds, which is strikingly similar to that observed in humans. The sanshool response latency is significantly slower than latencies to capsaicin or mustard oil. In addition, sanshool consumption fails to elicit the nocifensive responses of nose rubbing and wiping that are commonly observed following consumption of capsaicin or mustard oil (unpublished observations). Moreover, no differences were observed in the sanshool response latency between wild type and TRPA1-/-/TRPV1-/- animals. Thus, sanshool-evoked behaviors more likely result from tingling paresthesia, rather than painful irritation. This is consistent with the activation pattern of Aδ and Aβ fibers by sanshool, as well as with results from human psychophysical studies demonstrating that sanshool does not elicit pain sensations (Bryant and Mezine, 1999; Sugai et al., 2005). Although sanshool also activates a subset of C-fibers, it is unclear whether these C-fibers actually transmit pain signals. Several studies have demonstrated the existence of C-fibers that transmit information other than pain. For example, a recent study demonstrated the existence of unmyelinated C-fibers that code for pleasant touch sensations in humans (Loken et al., 2009). In addition, C-fibers that transmit sensations of brushing and itch have also been reported (Zotterman, 1939). Finally, specific labeling of neurons that express a Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor, MrgprB4, revealed a unique subpopulation of C-fibers that specifically innervate the skin, but not the viscera; these fibers are hypothesized to function as touch receptors, rather than nociceptors (Liu et al., 2007). Further analysis at the molecular and behavioral levels is required to elucidate the exact role of this new class of sanshool-sensitive C-fibers. Common among all sanshool-sensitive fibers is the presence of action potential bursting, which we observed in 29% of fibers. Bursting is exhibited by many neurons within the central nervous system, as well as some peripheral neurons. A short burst of action potentials may temporally summate to provide high-fidelity neuronal transmission (Williams and Stuart, 1999) or foster long term potentiation to strengthen neuronal synapses (Liu et al., 2008). In the peripheral nervous system, bursting has been described in trigeminal afferents in the brainstem that are thought to play a key role in the central pattern generator circuit regulating mastication in rodents (Brocard et al., 2006; Hsiao et al., 2009). Bursting is also associated with tingling paresthesia. Microelectrode recordings show robust bursting of sensory afferents in normal human subjects experiencing tingling paresthesia (Ochoa and Torebjork, 1980). In addition, neuronal recordings from patients suffering from activity-dependent tingling paresthesia showed robust bursting of myelinated, rapidly-adapting mechanoreceptors that increased with the degree of paresthesia. Finally, in rat models of diabetic neuropathy, robust bursting of medium diameter fibers increased in diabetic neurons as compared to wild type neurons (Jagodic et al., 2007). Indeed, tingling paresthesia is a common complaint of diabetic patients with neuropathy. We speculate that the bursting pattern may underlie the tingling sensation commonly associated with chewing Szechuan peppers. Activation of TRPA1 and TRPV1, and inhibition of the two-pore potassium channels KCNK3 (TASK-1), 9 (TASK-3) and 18 (TRESK) have been proposed as mechanisms by which sanshool activates neurons (Koo et al., 2007; Riera et al., 2009; Menozzi-Smarrito et al., 2009) (Bautista et al., 2008). However, we demonstrate that sanshool-evoked fiber responses are of similar prevalence and amplitude in the presence or absence of TRPA1 and TRPV1 selective antagonists. Likewise, sanshool-evoked behaviors were similar between wild type and TRPA1-/-/TRPV1-/- animals. These data suggest that neither TRPA1 nor TRPV1 mediate the excitatory effects of sanshool. In somatosensory neurons, expression and electrophysiological studies show the presence of KCNK18 channels (Dobler et al., 2007; Kang et al., 2008), but expression of KCNK3 and 9 have not been demonstrated; however, KCNK3 and 9 are expressed by keratinocytes in the skin (Kang and Kim, 2006). Thus, sanshool may act directly on KCNK channels in sensory neurons as well as in keratinocytes, which are known to modulate sensory neuron function (Koizumi et al., 2004; Lumpkin and Caterina, 2007) to induce tingling paresthesia. The bursting behavior observed in response to sanshool application is also consistent with a model of potassium channel blockade. Bursting in trigeminal neurons has been linked to the activity of Kv1 channels (Hsiao et al., 2009), and TEA-insensitive potassium channel(s) may contribute to burst firing (Brocard et al., 2006). However, analysis of KCNK-deficient mice is required to test this hypothesis. Recently, two other members of the KCNK channel family, KCNK2 (TREK-1) and KCNK4 (TRAAK), have been shown to regulate responses to thermal and mechanical stimuli in nociceptors (Maingret et al., 1999; Noel et al., 2009). Thus the KCNK family of channels may play key roles in a variety of mechanosensitive sensory fibers. Again, the analysis of mice lacking KCNK channels will be required to test this hypothesis. Our finding that sanshool robustly activates a distinct subset of D-hair, ultra-sensitive light touch receptors in the skin and targets novel, uncharacterized populations of Aβ and C-fiber nerve afferents shows that sanshool is an innovative tool for physiological and molecular studies. In addition, characterization of sanshool-sensitive mechanoreceptors represents an essential first step in identifying the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying tingling paresthesia that accompanies peripheral neuropathy and injury.   Schematic depicting distinct populations of stretch-sensitive and insensitive neurons. Stretch-sensitive neurons fall into two broad categories: Small-diameter cells (red circle) that are dually sensitive to hydroxy-α-sanshool (San) and capsaicin (Cap), and large-diamater cells (blue circle) that respond to hydroxy-α-sanshool, but not capsaicin. These cells likely correspond to high threshold nociceptors and low threshold proprioceptors, respectively. Stretch-insensitive neurons were predominantly of the small-diameter class and were represented by the subset of capsaicin-sensitive cells that also respond to mustard oil (yellow circle), and a cohort of menthol-sensitive cells (green circle). Circle size depicts relative diameter of the different neuronal subtypes. ------------- Food vibrations: Asian spice sets lips trembling Nobuhiro Hagura , Harry Barber and Patrick Haggard Published:07 November 2013 We showed that the tingling sensation induced by Szechuan pepper has a consistent and measurable frequency within the range of the RA1 tactile frequency channel. Furthermore, by using a frequency adaptation paradigm, we demonstrated that this tingling is probably mediated by the same pathway/RA1 frequency channel that processes frequency of the mechanical vibrotactile information. In experiment 1, we confirmed that the application of Szechuan pepper on the lips induces a tingling sensation, as has been shown previously [7,17]. However, some participants also agreed to the description ‘tingle’ when ethanol (four out of 12 participants) or even water was applied (three out of 12 participants). Interestingly, all seven of these reports involved control conditions experienced before the Szechuan pepper condition. This suggests that these responses may have reflected general tendencies to agree, rather than a discriminative response to the stimuli. By contrast, for the Szechuan pepper condition, 12 out of 12 participants agreed to the description ‘tingle’, regardless of the condition order. Furthermore, participants anecdotally described a qualitative difference between the tingling induced by the Szhechuan pepper and the other control conditions. Therefore, only the Szechuan pepper reliably induced the sensation having a specific tingling quality, consistent with involvement of a specific class of afferents. Previous studies have detected many varieties of compounds—sanshool—in the Szechuan pepper (α-, β-, γ-, δ-, hydroxy-α-, hydroxy-β-) [5]. Previous psychophysical studies using derivatives of these have identified hydroxy-α-sanshool as the compound most responsible for this unique buzzing and tingling [5,7]. From these previous reports, we believe that also in this study, the hydroxy-α-sanshool in the raw pepper activated somatosensory fibres [9] and induced the tingling sensation. However, our interest focused on the tingling sensation itself, not the molecular biochemistry that initiates it. Previous reports did not systematically investigate the perceptual parameters of this tingling sensation, and how these may relate with the activated somatosensory fibres. The results from the experiments 2–4 suggests that the information which elicits the tingling is conveyed by the light-touch RA1 fibres, which corroborates with the neurophysiological findings showing that the sanshool strongly activates those fibres in rats [9]. Other than the RA1 fibres, sanshool has been shown to also activate other sets of afferent fibres, including RA2, SA1, SA2 fibres and unmyelinated C-fibres [9]. Thus, there is a possibility that the overall sensation of sanshool tingling is a result of ‘blending’ of all of these afferent fibre activations [23]. However, RA2 fibres responding to higher frequency vibration are reportedly absent from the human orofacial area [15]. Mechanical frequency detection threshold on the lower lips was indeed reported to lack pacinian-type (RA2) like frequency sensitivity [24,25]. Further, slow adapting fibres are less responsive to sanshool than rapid adapting fibres [9]. Direct stimulation of orofacial SA1 and SA2 fibres by microneurography induces only sensations of sustained pressure, and not of tingling or vibration. By contrast, microneurographic stimulation could elicit sensations of flutter-vibration on the superficial skin site only when stimulating RA1 fibres [15], in agreement with our findings. Finally, although low threshold C-fibres have been shown to respond to mechanical stimulations [26,27], they are unlikely to contribute to perceived fast repetitive mechanical stimulation, owing to their slow conduction velocity and marked preference for slowly moving stimuli. Taken together, though Szechuan pepper may activate several fibre classes, we believe that the major contributor for the temporal component (tingling) of the tingling experience is owing to the activation of the RA1 frequency channel. Szechuan pepper creates the experience of vibratory sensation on the lips despite the absence of any mechanical vibration. Sanshool effects on other sensory channels may explain the accompanying feelings of cooling and numbing [7]. In experiment 4, we showed that the preceding prolonged mechanical vibration can reduce the perceived tingling frequency by Szechuan pepper compared with when followed by a static force. This indicates that the mechanical vibration and Szechuan pepper activates the same frequency channel, thus sharing the same tactile processing pathway. Importantly, the adapting vibration did not lead to any significant change in the sensitivity for discriminating frequencies. This suggests that the adaptor vibration did not lead to the strong reduction of the intensity of the signal, which should alter the discrimination ability, but rather worked to adapt the particular (RA1) temporal processing [20,21]. Adaptation to prolonged vibrotactile input has been reported at the receptor level [28], as well as in several central sites, including the cuneate nucleus [29], thalamus [30] and cortex [31]. RA1 type neurons are reported to exist in S1 [32] and are known to underlie frequency discrimination in the RA mechanical frequency range [33]. Therefore, adaptation of tactile processing at any of several stages of the afferent pathway may have affected the firing rate of the S1 neurons. Further studies are required to clarify this point. Nevertheless, the mechanical-to-chemical transfer of adaptation reveals the shared processing pathway between Szechuan pepper and mechanical vibration, and thus indicates that the Szechuan pepper-induced tingling experience is indeed a tactile frequency experience. Decomposing complex somatosensations into component units of neuronal activity is a critical step towards understanding how the brain constructs sensory experiences. Previous studies were able to investigate the minimal unit of somatosensory experiences using microneurographic stimulation of single afferent fibres [1]. However, natural stimuli generally activate large populations of neurons, each containing several afferents. By using an unusual chemical stimulus to activate a class of tactile receptor, we have been able to identify a discrete population of ‘labelled lines’ in the somatosensory system, based on their psychophysical properties. This offers a possibility of testing the minimal unit of somatosensation at a population level. Spontaneous firing of the population of RA afferent fibres and/or Meissner's corpuscle mechanoreceptor fibres are also thought to underlie the ‘pins and needles’ tingling sensation experienced after ischemia [34,35] or focal nerve compression [36]. As Szechuan pepper can activate populations of these same tactile fibres and induce similar sensations to paraesthesia, our result could provide insights into abnormal afferent fibre discharges in clinical cases of paraesthesia [37]. Finally, food is both an intense sensory experience and a primary carrier of human culture. Modern gastronomy recognizes the multisensory aspects of food, such as temperature [38], colour [39] and sound [40] on perception of flavour and taste. The specific somatosensory effects of Szechuan pepper shown here may provide a unique opportunity to investigate somatosensory contributions to taste perception. Szechuan pepper might boost taste by mimicking touch. [황교익 먹거리 파일] 조피? 젠피? 제피? 산초?… 추어탕에 뿌리는 흑갈색 가루의 정체는 '초피' 2014.02.28 17:15 추어탕집에만 가면 흑갈색 가루 때문에 한바탕 혼란이 인다. 사람들이 저마다 다른 이름으로 부른다. 초피가 맞다. '조피', '젠피' '제피' 등은 사투리이다. 그러면 '산초'는? 산초는 또 다른 식물이다. 추어탕에 넣는 향신료 '초피'는 초피나무 열매다. 한반도 남부 지방과 동해 연안에 자생한다. 키가 3m 정도 자라고 가지에 가시가 있다. 5~6월에 꽃이 피고 8~9월에 열매를 맺는다. 향은 입안에서 '화~' 하고 터진다. 혀를 얼얼하게 하는 것은 후추와 비슷하나 후추와 달리 신맛이 강하다. '초피'와 많이들 헷갈리는 '산초'는 산초나무 열매다. 산초나무는 중부 내륙 지방에 자생한다. 초피와 생김새는 비슷하나 그 맛과 쓰임은 완전히 다르다. 산초는 얼얼하지도 시지도 않다. 향은 비누 냄새 비슷하다. 무엇보다도 산초는 향신료로 쓰지 않는다. 열매의 씨앗에서 기름을 짠다. 초피와 산초는 분명히 다른 식물인데도 많은 사람이 초피를 산초라고 부르고, 산초를 초피처럼 쓴다. 추어탕 전문점에서 추어탕에다 산초 가루를 털어 넣는 황망한 일도 벌어진다. 이러한 혼란은 예전엔 없었다. 초피와 산초의 자생지가 다르기 때문에 초피는 남부 지방에서 향신료로, 산초는 중부지방에서는 기름으로 썼다. 초피와 산초를 혼동하게 된 건 일본의 영향이다. 한국의 초피를 일본에서는 '산쇼(山椒·산초)'라 한다. '산쇼'는 일본 음식에 약방 감초처럼 쓰이는 향신료이다. 우동집 식탁에 놓여 있는 시치미(七味)에도 이게 들어 있다. 생선회 곁에, 국물 음식 위에 '산쇼(초피)'의 어린잎을 올리기도 한다. 일본에서 '산쇼'를 접한 사람들이 한국의 초피를 '산초'라 부르는 일이 잦아졌고, 심지어 초피 대신 '산초'를 쓰는 일까지 생긴 것이다. 언어의 혼란은 어쩔 수 없는 일이지만, 제발 추어탕집 식탁에서 비누 냄새 나는 산초를 만나는 일만은 막고 싶다. 최근 초피에 또 하나 혼란이 더해지고 있다. 이번에는 '중국발'이다. 쓰촨 요리에 쓰이는 '화자오(花椒·화초)'다. 훠궈(火鍋·중국식 샤부샤부) 등 쓰촨 요리가 근래에 인기를 얻으면서 한국인들 사이에서 차츰 익숙해지고 있는 이름이다. 어떤 사람들은 이 '화자오'를 '중국 산초'라고 설명한다. 그러니 '화자오'는 한국의 초피와 거의 같은 식물이다. 차이가 있다면 한국 초피보다 신맛이 덜하다는 것. 얼얼한 맛에서는 동급이다. 혼란을 막자면 이렇게 기억하면 된다. '한국의 초피(椒皮), 일본의 산쇼(山椒), 중국의 화자오(花椒)는 같은 향신료다. 그리고 한국의 산초는 향신료가 아니다.' '초피'의 영어 이름은 'Sichuan pepper(쓰촨 후추)'다. 쓰촨 요리를 통해 서양에 알려졌기 때문이다. '초피'는 또 'Chinese pepper(중국 후추)'라고도 하며, 일식을 통해서도 전파되면서 'Japanese pepper(일본 후추)'란 이름도 얻었다. 동양 특산인 데다 후추에는 없는 독특한 향을 지니고 있어 서양에서는 '동양의 신비한 후추'로 여기기도 한다. 'Korean pepper(한국 후추)'는 없느냐고? 이 이름으로 구글링을 하면 고추만 검색된다. 이마저도 한국인이 짧은 영어 솜씨로 올린 것이다. 참 묘하게도 한국인은 초피를 꺼린다. 남부의 일부 지방에서, 그것도 토속적 입맛을 지닌 사람들이 추어탕에나 넣어 먹는 이상야릇한 열매 정도로 여긴다. 그러니 그 이름 따위에 관심이 갈 리가 없다. 그런데 일본을 보니 '산쇼'라는 것이 있고, 그것참 묘하다 싶어 '산초, 산초' 하다가 이제는 중국 쓰촨 요리 먹다 '화자오'를 발견하고선 '중국 산초'라 하고…. 매년 늦여름이면 일본 상인들이 지리산에 온다. 초피를 수매(收買)하기 위해서이다. 1㎏에 6000원 정도의 헐값에 거둬 간다. 한국인이 하찮게 여기니 쌀 수밖에 없다. 일본에서는 이 지리산 초피를 최상품으로 여긴다. 신맛이 특히 강렬하기 때문이다. 그러든 말든, 우리는 그게 초피인지 산초인지 분간도 못 하고 있으니…. |

||||

|

|

|||